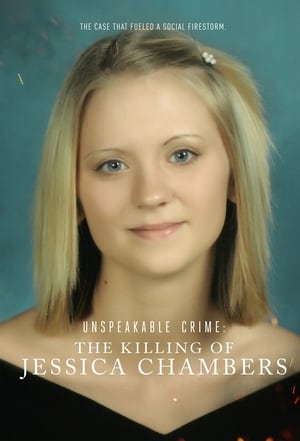

Unspeakable Crime: The Killing of Jessica Chambers

**_A decent overview of a savage murder, a town torn apart, two families destroyed, and the dark side of social media_** > _Jessica was murdered last December, but people from all over the country still convene on forums and in Facebook groups to argue about who killed her and why. Private investigators seeking the now $54,000 reward for information leading to Jessica's killer have trawled the county for clues, but the dozens of diehards who post every few hours about Jessica's case have never even been to the scene of the crime: Courtland, Mississippi, population 512._ > _These people_ – _who range from C-list conservative bloggers to gluten-free bakers from Montreal, boat enthusiasts from Florida, and grocery-coupon collectors from North Carolina – claim to want #JusticeForJessica above all. Instead, they've terrorised her formerly sleepy hometown with their relentless demands for answers to their specious theories. In the process, they've spread rumours that have filtered into real life, igniting racial tensions, digging up old skeletons, and reawakening feuds. For these amateur detectives, Jessica's death isn't a mother's tragedy. It's a pastime._ - Katie J.M. Baker; "Troll Detective"; _BuzzFeed_ (June 25, 2015) > _When it all happened and they said Quinton had something to do with it, we said we doubt it, but okay. If that's who they gonna send to prison, bye. Do I think Quinton had the intelligence to do something like that? No I don't. Boy can't write. And being able to get rid of the evidence by hisself? Impossible. But I think Quinton will be the fall guy for this because when something lands in the state of Mississippi, things have to go away real fast. That case became worldwide; it wasn't just some Mississippi case that we could actually sweep under the rug and, "Shush, be quiet". What's gonna happen is they gonna give it some time and then forget about him, case closed, that's out the way now, somebody went to prison for the murder. But let me say this, you have to be a real dumb black man to burn up a white girl in the state of Mississippi._ - Demarcio Coleman (former gang member and drug dealer) > _I don't put much faith in Panola County's law enforcement. In my opinion, it's an old fashioned witch-hunt. Quinton just looks like the obvious one, so let's go ahead and pin it on him and be done with it. Now, they're so far into it, I don't think they would change it, just for the fact of it would make them look bad._ - Eddie Edison (volunteer firefighter) > _This is_ not _your guy._ - Ben Levitan (telecommunications expert) > _Do we ever think back and say we should have done things another way? Sure we do. I mean, it's always a learning experience._ - Lt. Dennis Darby (Panola County Sheriff's Department) On the evening of December 6, 2014, in the small town of Courtland, Mississippi (population just over 500), the fire department responded to reports of a burning car on a quiet rural road. As they fought the flames, one of them saw someone approaching from the nearby woods; a young girl, wearing only her panties, her entire body burnt beyond recognition, her hair singed away to nothing. Her name was Jessica Chambers (19) and she had been inside the car when it was doused in accelerant and set on fire. Incredibly, despite having third-degree burns to 93% of her body, Jessica was lucid enough to tell multiple first-responders that "Eric" had set her on fire. But who was Eric? Why did he do this? Why would anyone kill someone in this manner? Jessica died in the early morning hours of December 7, but her death was only the prologue to a story which would rip a town apart, destroy two families, lead to two trials, expose both investigative and prosecutorial ineptitude, and highlight a dark and dangerous side of social media. And it's a story which is unresolved even now, almost six years later. Inspired by Katie J.M. Baker's June 2015 _BuzzFeed_ article, "Troll Detective" and directed by celebrated documentarian Joe Berlinger (_Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills_; _Metallica: Some Kind of Monster_; _Whitey: United States of America v. James J. Bulger_), _Unspeakable Crime: The Killing of Jessica Chambers_ aired on Oxygen in North America and Sky Crime in the UK and Ireland. Originally a five-part series (the feature-length first episode was split in two for international markets), an additional episode was hastily added when the story took an unexpected turn in the middle of the broadcast. Despite its title, however, _Unspeakable Crime_ isn't really a deep dive into why Jessica was killed or who may have done it. Rather, it's a courtroom drama, following the trial of the man who law enforcement believes lit the match – Quinton Tellis (26 at the time). It's a solid enough overview of the case, although some of the more interesting revelations are found, strangely enough, only in the accompanying podcast of the same name. A tad repetitive and not especially interesting from an aesthetic point of view, the show nevertheless does a good job of laying out the facts and illustrating just how many lives this horrific crime impacted, and how profoundly it impacted them. A former cheerleader, Jessica had had a very close relationship with her family until her brother Allen was killed in a road accident in 2012. After his death, Jessica lost interest in cheerleading and school in general, started smoking and selling weed, and became associated with several local gang members (although she herself was never in a gang). Early in 2014, Jessica spent time at Leah House, a "restoration home for women", and according to her mother Lisa Daugherty, she had committed to turning her life around and pursuing her dream of becoming a nurse. Up to a point, Jessica's movements on December 6 are known. She spent the morning with her friend Kesha Meyer and Quinton Tellis, whom she had only recently met, and with whom she may or may not have had a sexual relationship. Tellis had only been out of county jail a few months, having served time for simple assault, possession of narcotics, and resisting arrest. After Tellis dropped her home on December 6, Jessica slept for a few hours, before receiving a text message later that afternoon. Telling her mother she was going to get something to eat, she left the house around 17:00. About a half-hour later, surveillance footage showed her at a local convenient store. Her cell phone data then shows she travelled to the next town over, Batesville, at around 18:00, returning to Courtland at 18:30. At 18:45, she called Lisa and said she'd be home soon. It remains unknown exactly what happened from this point forward, as her phone went dark, and she would not be seen again until she approached firefighters at around 20:15. As she was being treated by first-responders, Jessica repeatedly said that someone named either "Eric" or "Derrick" had set her on fire. However, she gave no surname and the only additional information she provided was that the man was black. No one in her phone was named Eric or Derrick, and none of her family or friends knew of anyone by that name. With this in mind, law enforcement looked at every African-American named Eric or Derrick in Panola County, with none proving a viable suspect. As they knew he was with her on the day she died, they also questioned Tellis, but at the time, he wasn't under any suspicion (and he also passed a polygraph). Fast-forward to 2015, at which point police are still without a suspect, with each investigative avenue leading nowhere. It was only when they went back over the cellphone data that they saw a connection to Tellis they'd missed in 2014 – his phone data placed him in the same immediate area as Jessica in the hours leading up to her death, and his phone went dark for the same period as hers, from around 18:45 until around 20:15. When they attempted to locate Tellis, police learned he was in prison in Louisiana. Earlier in 2015, he had been convicted of using a stolen debit card and sentenced to ten years for fraud. What makes the situation more interesting, however, is that the card belonged to Meing-Chen Hsiao, a Taiwanese student at the University of Louisiana at Monroe, who was tortured and killed just days prior to Tellis using her card (which he asserts he purchased from a street-level drug dealer). CCTV footage shows Hsiao and Tellis together at a Wal-Mart the day before she was believed to have been killed, and in the days leading up to her death, Tellis was seen coming and going from her apartment multiple times (he would be indicted for her murder in May 2019). When police questioned Tellis about his movements on the day of Jessica's death, he changed his story several times. Initially, he claimed not to have seen her after dropping her off at her house around 11:00, saying he was in Batesville with a friend at the time Jessica's car was set on fire. This alibi proved false, however, as the friend was actually in Nashville at that time, and Tellis wasn't with him. Additionally, security camera footage from the store that Jessica visited at 17:30 showed Tellis there at the same time and then showed him returning to the store at 20:26, roughly ten minutes after firefighters had arrived at the scene of the fire. In this later footage, Tellis is wearing different clothes than in the earlier footage. Confronted with this, Tellis changed his story again, saying that he and Jessica went to Batesville to get something to eat, and upon arriving back in Courtland, they parked in his driveway until 19:00, at which point she drove away. Investigators also discovered that in the hours immediately after her death, Tellis had deleted all communication with Jessica from his phone, even going so far as to remove her from his phonebook entirely. Investigators believe that as Jessica and Tellis sat in her car in his driveway, he tried to have sex with her and she resisted (several times in the days before her death, he had contacted her asking for sex, but she had turned him down each time). They posit that he choked her in a rage, rendering her unconscious (incredibly, Jessica was never examined for signs of sexual assault so it's unknown whether she was raped before her death). Believing that he had killed her, Tellis drove her car to where it would later be found and then ran to his sister's nearby home (the keys to Jessica's car were found on the road between the crime scene and the house). He borrowed his sister's car, drove back to his own home, got a can of gasoline, drove back to the car, set it on fire with Jessica inside (still unaware she was alive), returned to his sister's, changed clothes, and was then seen on CCTV at 20:26. It's a very tight timeline, with some arguing he wouldn't have been able to do everything in the time available, whilst others argue it's just about possible. In February 2016, Tellis was indicted on a capital murder charge, with his trial beginning in October 2017, which is roughly where the series begins. Hosted by Beth Karas, _Unspeakable Crime_ features an impressive cross-section of people involved with the case, giving us multiple perspectives. Interviewees including Lisa Daugherty (Jessica's mother), Ben Chambers (her father), Amanda Prince and Ashley Chambers Sipes (her sisters), Debbie Chambers (her stepmother), Rebecca Tellis (Tellis's mother), Laqunta Tellis and Shaneeka Williams (his sisters), Darla Palmer and Alton E. Peterson (his defence team), John Champion (DA, Panola County), Jay Hale (Asst. DA), Maj. Barry Thompson (lead investigator, Panola County Sheriff's Department), Lt. Edward Dickson (Thompson's second-in-command), Sheriff Dennis Darby and Chief Deputy Chris Franklin (Panola County), Lt. Jimmy Anthony (Vice President, Mississippi Association of Gang Investigators), Melissa Meek-Phelps (Circuit Clerk, Panola County), Eddie Edison (volunteer firefighter and the first on the scene of the crime), Neal Johnson (Asst. DA (Ret.), Monroe County), Chief Deputy Otis Griffin (Coahoma County), Benniea Felder (juror), Katie J.M. Baker (_BuzzFeed_), Janice Broach (WMC-TV), Therese Apel (_The Clarion Ledger_), Ashley Mott (_Monroe News-Star_), John Howell (_The Panolian_), Melissa Jones (LawNewz), Demarcio Coleman (former gang member and drug dealer), Professor Greg Hampikian (DNA expert and Founder/Director of the Idaho Innocence Project), Ben Levitan (telecommunications expert), George 'Boone' Mister (Jessica's friend, who was targeted by online sleuths), Charlotte Wilkerson (another friend, who was also targeted), and multiple Courtland residents, some of whom believe Tellis to be innocent, whilst others are convinced of his guilt. One of the show's main themes is the pernicious effects of social media. Within days of her death, multiple Justice for Jessica and Jessica's Revenge groups had appeared on Facebook. Without a shred of evidence, some amateur sleuths suggested Ben had killed her because he disapproved of miscegenation, and at the time of her death, Jessica was dating an imprisoned African-American, Travis Sanford. Others focused their ire on Lisa's perceived lack of parenting skills. When Tellis was accused of the crime, his family became the target for hatred and harassment. Of course, as Baker points out, none of these armchair detectives actually knew any of the people involved, had access to any of the case files or evidence, or had ever visited Courtland. But that didn't stop them attacking the Chambers family, abusing the Tellis family, and even turning on Jessica herself when it emerged she smoked and sold weed, with some speculating that her death may have been gang-related. In an especially lucid example of the toxicity of online herd mentality, Ali Alsanai, the clerk at the store where Jessica was last seen, was forced to leave Panola County when he received death threats after right-wing commentators began to accuse him of the murder. Their evidence? He's of Middle-Eastern descent. As this might suggest, aside from social media-related issues, the other big theme is race. One of the first comments in the first episode is that Tellis's trial has triggered a pseudo-race war in Courtland, with most blacks believing him innocent and most whites believing him guilty. With this in mind, there are many references to an ominous feeling in the air, as groups protesting Tellis's innocence and groups asserting his guilt gather at the courthouse in Batesville. This feeling only gets stronger as the trial approaches its conclusion (on the day of the verdict, police formed a barrier at the front of the court, just in case). Within the trial, the show's main focus is the same thing that Tellis's defence team focused on – the fact that Jessica said that "Eric" or "Derrick" had set her on fire. This was _the_ major hurdle that the prosecution had to try to overcome; by suggesting that Tellis was the murderer, it meant that they had to discount the testimony of at least eight first-responders, all of whom heard her say "Eric" or "Derrick". To this end, they called to the stand Dr. William Hickerson, a plastic surgeon specialising in burns, and Carolyn Higdon, Professor of Communication Sciences and Disorders at the University of Mississippi. Both testified that Jessica would have found it difficult to impossible to say anything clearly, due to her injuries, and both outright reject the notion that she said "Eric" or "Derrick". Prosecutors instead suggest that the proliferation of the name amongst first-responders was a kind of inverted Chinese whisper – one first-responder thought they heard something that sounded like "Eric", and suddenly eight people claimed to have heard it. As Karas points out, however, when eight of your own witnesses testify that a murder victim gave up the name of her killer, and it isn't the name of the guy on trial, you've got a serious obstacle to overcome. With that in mind, the show spends a lot of time illustrating the often gaping holes in the prosecution's case and the inadequacies of the police investigation. For example, Lt. Dickson is shown having a truly bizarre exchange with Peterson on the witness stand – when Peterson asks him where he was when he got the call about the fire, he says he was at home in Sardis, a town about 18 miles north of Courtland. However, when Peterson asks him how long it took him to get to Courtland, he says that not only does he not know how many miles the journey is, he also says he has no idea how long the drive takes ("_I've never clocked myself going to work_"). As an incredulous Ben says, this is a drive that Dickson has made twice a day for about 22 years, pointing out that his own seven-year-old daughter (Jessica's half-sister) would be able to tell you how long it takes her to get to school. The show is also critical of how the police processed the crime scene, arguing that a larger area should have been roped off (the actual crime scene was the car, nothing outside it), that dogs should have been used to search for ignitable liquids, that fire-trained CSI officers should have been called in, that the car should have been left at the scene for longer (it was moved to the police lot the night of December 6), that the surrounding woods should have been searched either that night or at first light (they weren't searched until the following week), and that Jessica should have been examined for signs of sexual assault. A big area of criticism concerns DNA found on Jessica's car keys. Although the prosecution says on multiple occasions that Tellis's DNA was on the keys, during cross-examination, their own DNA expert, Catherine Rogers, explains that this isn't entirely accurate. In actuality, the DNA of four men was found on the keys, and Rogers couldn't exclude the possibility that some of the DNA was Tellis's. Which is, of course, a very different thing than saying his DNA is on them. The podcast goes into this in a lot more detail than the show, but, in essence, Hampikian explains that Rogers used a Y-STR test, which didn't exclude Tellis, when an autosomal STR test (which did) should have been presented in court; > _in this case, you had a general inclusion with the Y-STR, kind of like a first initial, but then when you drill down with the very precise autosomal STR test, you have what is essentially a social security number. That's why we prefer that autosomal STR test. If a suspect is included or cannot be excluded from a mixture of Y-chromosomes and a Y-STR test, but they are excluded by an autosomal STR test, they're excluded, period. No further testing is needed. It's disingenuous, to say the least, to keep someone in an inclusion when you have a more precise test that absolutely excludes them. So why isn't that information in the report? I don't understand it. The autosomal test is the more precise test, end of story. You don't even talk about your general screening test that includes potentially millions of people. You only should talk about the more precise test. It's kind of like, you might think you're pregnant, but you're not going to tell your friends if you've taken a pregnancy test that says you're not pregnant; you're not going to continue to tell them, "I think I'm pregnant". When you have better information, you defer to the better information, and in this case, the better information is the autosomal STR exclusion, not the DNA mixture inclusion – in this case, Tellis was excluded by the autosomal test, a point which wasn't included in the written report._ Significant and thought-provoking stuff. The other major area critiqued by the show is the cellphone data that the prosecution argued proves Tellis and Jessica were in the same place at the same time right before she was set on fire. In short, it doesn't. At all. The investigation into the cellphone data was led by Paul Rowlett, an Intelligence Specialist with the Department of Justice. For Jessica's phone, he looked at records for the Range to Tower (RTT), a Verizon-exclusive technology, which can be used to pinpoint a phone when it pings the nearest cell tower. Rowlett says that RTT records prove Jessica was at Tellis house until about 19:30. However, Tellis's phone was AT&T, who use a Network Event Location System (NELOS), which gives the direction from which a phone is pinging a tower, but not the distance, thus making it impossible for the data to prove Tellis and Jessica were together. According to Levitan, > _the state has a theory and they've taken the cellphone evidence, not looking at it objectively, and manipulated it in a manner to fit the theory. The cell tower that she's connected to when she makes the call to her mother does not cover Tellis's house, does not cover that area whatsoever. When Jessica made this phone call, she was connected to a cell tower that was in Pope, which is three to four miles south of Quinton's home. As such, that call excludes her from being at Tellis's house at that time_ [...] _if law enforcement had come to me, and said "can you analyse the cell phone data and tell us were these guys together", I would have said "you're shifting the data to make the evidence for your theory. This is_ not _your guy"_ [...] _In some cases, they may have been in an overlapping area, but for the most part, they were not together, period. Based on science, based on the cellphone data we objectively looked at, what Rowlett said is not true. I cannot put Quinton Tellis in an area smaller than 14 square miles. That's what the data shows. That it was presented to the jury as "irrefutable evidence" that Tellis was with Jessica is completely false._ So, much like the DNA, not only does the evidence not confirm Tellis's guilt, it actually suggests his innocence. Levitan also discovered that during the hour when the prosecution claim both Tellis and Jessica's phones were dark, Tellis actually sent three texts, but he did so using an online server rather than via his phone. Strangely, however, Tellis defence team don't call a single witness, so there's no one to refute or even challenge Rogers and Rowlett's testimonies. This is something the show skims by, disappointingly letting Palmer and Peterson off the hook, which is strange when one considers the length the show goes to probe and present the evidence. The show also looks at some interesting side-issues, albeit fairly superficially. For example, Tellis told police that a registered sex-offender named Derrick Holmes was stalking Jessica. He was ruled out by investigators as a possible suspect, but the reason they discounted him leaves Karas somewhat aghast – he was apparently at home rubbing his mother's feet at the time the car was set on fire, with seemingly little to back this up, other than the word of his mother and some additional family members. Another issue is that the week she was killed, Jessica had told Lisa, "_these bitches think I'm snitching, but I'm not_", although she refused to elaborate on who "these bitches" were. Ben was a mechanic with the local police department, and according to Jessica, because of that connection to law enforcement, she had been pegged a rat. However, the show never really goes anywhere with this fascinating line of enquiry. A third issue is that of a mysterious black male who was present at the crime scene as firefighters fought the blaze, even speaking to one of them (who he totally weirded out). According to witnesses, he was acting very strangely and seemed fascinated with the fire. The show states that this man was identified and cleared of any involvement, but it gives us no further information. Some other criticisms I'd have would include how aesthetically bland the show is and a tendency towards repetition, especially from episode to episode, as each episode tends to repeat material from the previous episode. Additionally, too much valuable information is covered exclusively in the podcast. _Unspeakable Crime: The Killing of Jessica Chambers_ isn't so much about the savage murder itself as it is about the reverberations of that murder – race relations compromised, a town torn apart, families destroyed. And problems notwithstanding, this is a decent overview of the subject.