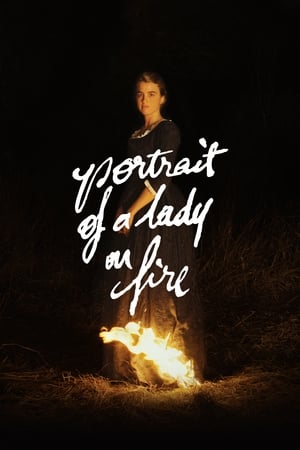

Portrait of a Lady on Fire

Céline Sciamma, writer and director of “Portrait of a Lady on Fire,” calls her period film a “manifesto on the male gaze.” This is the most accurate, elegant description of her story of a romance between two French women in the late 1700s. This is an impeccably detailed, beautifully acted, refined drama with a strong feminist angle that’s as stirring as it is thought-provoking. Marianne (Noémie Merlant) is commissioned to paint the wedding portrait of Héloïse (Adèle Haenel), a young woman who has just left the convent. Because Héloïse is a very reluctant bride-to-be, Marianne arrives under the guise of companionship, observing the smallest of details about the woman by day and secretly painting her by firelight at night. As the two women spend their days with one another, intimacy and attraction grow, and the portrait becomes a symbol of the intensity of their love. The lead performances are mannered and structured in the most effective way. The strong desire between the two women is manifested in a gaze or careful examination of a wisp of hair or the way Héloïse crosses her hands. There’s a quiet intensity to the emotional and physical intimacy between these two women, making this love story’s end feel all the more heartbreaking. This is mostly an all-female film, and the men briefly seen on screen play little importance. Rounding out the characters are Héloïse’s mother (Valeria Golino) and housekeeper Sophie (Luàna Bajrami), who both fill critical roles in the story as the film explores issues affecting women at the time, including arranged marriages, career expectations, and health concerns. The film itself is absolutely stunning, with gorgeously romantic and lush cinematography by Claire Mathon setting a sensual tone that complements the story. The artistry is outstanding, making “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” one of the most powerful, intellectual dramas of the year.