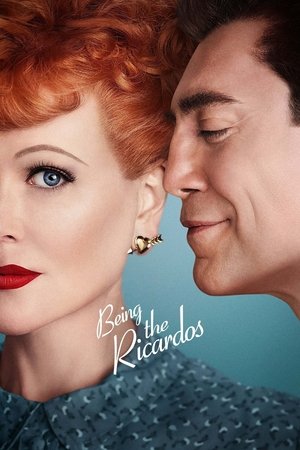

Being the Ricardos

There are two lines of dialogue in Being the Ricardos that really caught my attention. One is “I literally said that 30 seconds ago,” and the other is “It takes fewer words to say that than the truth.” This film feels like a lot of the former when it should be more of the latter. Why does a movie called Being the Ricardos spends so much time on Ethel/Vivian Vance (Nina Arianda) and Fred/William Frawley (J.K. Simmons), whom nobody cared about 70 years ago, and no one cares about today? Speaking of redundant characters, writer/director Aaron Sorkin aims to give the film a documentary feel with asides set in the present day in which people involved with the production of I Love Lucy talk about it — kind of like in Reds, except that Reds worked because the individuals interviewed were who they were supposed to be, and not actors playing aged versions of people who are already played by other, younger actors in the main narrative. These parentheses do little but repeat things we have just seen, or are about to see, dramatized in the scene immediately before or after (either show or tell — preferably show —, but not both); they have no value other than as filler, and filler is exactly the last thing a two-hour-plus movie needs. Ostensibly, the plot revolves around a typical week on I Love Lucy’s set, including rehearsals, filming, etc. — and indeed a fly-on-the-wall behind-the-scenes approach to the inner workings of one of the most influential TV shows history should be able to generate more than enough interest on its own. Sorkin, however, brings up momentous events only to gloss them over. For example, Lucille Ball (an unrecognizable Nicole Kidman) and Desi Arnaz (Javier Bardem in the perfect role for his routine massacre of the English language) are having a second child (although their firstborn is so irrelevant to Sorkin that she is named a couple of times and seen only once), and they both decide that Lucy and Ricky will have a kid too; this aspect is mentioned, and even discussed, but never really addressed, and the reason for this omission is obvious: since, as I already pointed out, the central section of the film takes place over the course of a week (with flashbacks that become an unnecessary distraction), her pregnancy never gets a chance to be truly incorporated into the plot. Another incident that Sorkin touches on but doesn’t even begin to explore is when Ball was accused of being a communist. This is treated as no more than a minor annoyance, but surely it should have affected her career much more than the film lets on —and if it didn’t, what was it that made Ball so special that this didn’t even qualify as a bump in the road? All things considered, Being the Ricardos devotes way too much time to extracurricular activities. Sacrificing length for depth might have turned this 125-minute behemoth into a much more manageable 90-minute romp.