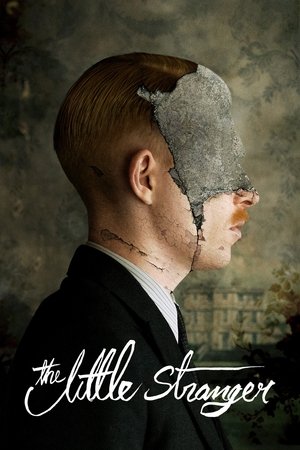

The Little Stranger

_**An "atmospheric character drama" without any atmosphere, and precious little drama**_ > _The subliminal mind has many dark, unhappy corners, after all. Imagine something loosening itself from one of those corners. Let's call it a - a germ. And let's say conditions prove right for that germ to develop - to grow, like a child in the womb. What would this little stranger grow into? A sort of shadow-self, perhaps: a Caliban, a Mr Hyde. A creature motivated by all the nasty impulses and hungers the conscious mind had hoped to keep hidden away: things like envy and malice and frustration._ - Sarah Waters; _The Little Stranger_ (2009) I remember when I first saw Paul Thomas Anderson's _Inherent Vice_ (which I loved) in 2014, a colleague of mine (who hated it) was unable to grasp why I had enjoyed it so much. I tried to explain that if he had read Thomas Pynchon's 2009 novel, he'd have appreciated the film a lot more, to which he posited, "_one shouldn't have to read the book in order to appreciate the film._" I think I mumbled something about him being a philistine, and may have thrown some rocks at him at that point. So imagine my chagrin when I watched the decidedly underwhelming _The Little Stranger_, a huge box office bomb ($417,000 gross in its opening weekend in the US), and easily the weakest film in director Lenny Abrahamson's thus far impressive _oeuvre_. You see, I really disliked it, but the few people I know who have read Sarah Waters's 2009 novel (which I have not), have universally loved it, telling me I would have liked it a lot more if I was familiar with the source material. To them, I can say only this – "_one shouldn't have to read the book in order to appreciate the film._" It seems my colleague was right after all. I hate that. The film is set in Warwickshire, a West Midlands county in England, in 1948, where Dr. Faraday (Domhnall Gleeson) is a country physician whose life is going nowhere fast. Born into humble beginnings, ever since he was a child, he has wanted to be a member of the gentry. In 1919, he attended a fête at the opulent Hundreds Hall estate, owned by the aristocratic Ayers family, where his mother worked as a maid, and ever since he has been quietly obsessed with the house. However, by 1948, Hundreds has lost its lustre, is in a state of disrepair, and is now home to only four people – Angela Ayers (Charlotte Rampling), matriarch of the Ayers dynasty, and who never recovered from the death of her eight-year-old daughter, Susan, many years previously; Caroline (Ruth Wilson), her daughter; Roderick (Will Poulter), Angela's son, a badly-burned former RAF pilot suffering from PTSD; and Betty (Liv Hill), the maid. When Betty takes ill, Faraday is summoned, almost immediately learning that the family is in a dire state, with Angela unable to balance their diminished financial situation with the social responsibility of maintaining the estate. Betty also intimates to Faraday that "something" is not right in the house. Offering to treat Roderick's painful burns, Faraday soon ingratiates himself into the family, and becomes a semi-permanent presence in Hundreds. However, that's when things start to go wrong; a child is mauled by a previously passive dog, a mysterious fire guts the library, and noises can be heard throughout the house. As Caroline determines to leave, Faraday attempts to convince everyone there is nothing supernatural happening. Nevertheless, Angela is certain the spirit of Susan is with them; Caroline believes it all has something to do with Roderick's deep unhappiness; Roderick asserts it is something that wants to drive him mad and deprive him of his birthright; and Betty believes it is the malevolent spirit of a former domestic servant. Meanwhile, Faraday and Caroline become romantically involved. As mentioned above, I haven't read the novel, so most of the proceeding comments are in relation to the film only. Aspiring to blend elements of "big house"-based mystery narratives such as Charlotte Brönte's _Jane Eyre_ (1847), Charles Dickens's _Great Expectations_ (1861), and Daphne du Maurier's _Rebecca_ (1938), with more gothic-infused ghost stories such as Edgar Allan Poe's "The Fall of the House of Usher" (1839), Henry James's _The Turn of the Screw_ (1898), and Shirley Jackson's _The Haunting of Hill House_ (1959), _The Little Stranger_ is not especially interested in the supernatural aspects of the story _per se_. In this sense, Abrahamson and screenwriter Lucinda Coxon have, to a certain extent, created an anti-ghost story which eschews virtually every trope of the genre. More a chamber drama than anything else, the film has been done absolutely no favours whatsoever by its trailer, which emphasises the haunted house elements and encroaching psychological dread (the fact that the film was pushed back from intended release dates several times suggest the studio themselves didn't know quite what they had on their hands). Indeed, to even mention the supernatural elements at all is essentially to give away the last 20 minutes of the film, as this is where 90% of them are contained. Waters herself has stated she does not consider the novel a ghost story. Instead, she was primarily interested in the rise of socialism in England, the landslide Labour victory in the 1945 general election, and how the now fading nobility was dealing with the decline in their power, influence, and financial opulence; > _I didn't set out to write a haunted house novel. I wanted to write about what happened to class in that post-war setting. It was a time of turmoil in exciting ways. Working class people had come out of the war with higher expectations. They had voted in the Labour government. They wanted change. So it was a culture in a state of change. But obviously, for some people, it was a change for the worse._ With this in mind, the main theme of the film is Faraday's attempts to ingratiate himself with the Ayers family, to transform himself into a fully-fledged blue blood, even when doing so goes against his medical training; his commitment to his own upward mobility is far stronger than his commitment to the Hippocratic Oath. He is immediately dismissive of the possibility of any supernatural agency in the house, and, far more morally repugnant, he does everything he can to convince those who believe the house is haunted that they are losing their minds, that the stress of what has happened to the family has pushed them to the point of a nervous breakdown. He's also something of a passive-aggressive misogynist, telling Caroline, "_you have it your way – for now_", and "_Darling, you're confused_". For all intents and purposes, Faraday is the villain of the piece, which is, in and of itself, an interesting spin on a well-trodden narrative path. However, for me, virtually nothing about the film worked. Yes, it has been horribly advertised, and yes, it is more interested in playing with our notions of what a ghost story can be, subverting and outright rebelling against the tropes of the genre. I understand what Abrahamson was trying to do (after all, my all-time favourite horror movie, Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez's _The Blair Witch Project_ (1999) is all about psychologically disturbing the audience, with not a jump scare in sight), however, so too does _The Little Stranger_ shun the standard alternative to jump scares – creeping existential dread – and as a result, it remains all very subtle, and all very, very boring – the non-supernatural parts of the story give us nothing we haven't seen before, and the supernatural parts simply fall flat (the "twist" at the end is also incredibly predictable). One of the main issues for me is Faraday's emotional detachment. I get that he's the ostensible villain, so we're not meant to empathise with him, and, as an unreliable narrator, his very role is to objectively undermine the subjective realism of the piece, and disrupt the smooth path of the narrative transmission (the same role performed by the Second Mrs. de Winter in _Rebecca_). However, Gleeson/Faraday practically sleepwalks his way through the entire film, getting excited or upset about (almost) nothing; on a stroll through the estate with Caroline, she apologises for dragging him out into the cold, and he replies, "_Not at all. I'm enjoying myself very much_", in the most dead-tone unenthusiastic voice you could possibly imagine, sounding more like he is having his testicles sandpapered (this part also elicited the film's only laugh at the screening I attended). So I know detachment is precisely the point, but, firstly, we've seen Gleeson play this exact same character before – all brittle, buttoned-down intellectualism – and secondly, he comes across as more robotic than detached, and after twenty minutes, I was thoroughly bored of him, and just stopped caring. Indeed, all of the characters are somewhat buttoned down, but Rampling, Wilson, and Poulter all give more nuanced performances than Gleeson. Partly because of this, and partly because of Coxon's repetitive script, the film is just insanely and unrelentingly dull. Now, I don't mind films in which nothing dramatic happens (Chloé Zhao's _The Rider_ (2017), which barely has a plot, is one of my films of the year), but in _The Little Stranger_ nothing whatsoever happens at all, dramatic or otherwise. By way of comparison, check out Oz Perkin's _I Am the Pretty Thing that Lives in the House_ (2016), a similarly themed film which shuns jump scares but whose encroaching sense of dread creates a potently eldritch tone, something sorely lacking in _The Little Stranger_. Instead, the script just goes round and round, through the motions; "_this house is haunted_" – "_no, you're just tired_" – "_you're probably right_" – "_I am, have a lie down_" – "_okay. Wait, this house is haunted_" – "_no, you're just tired_", etc.; wash, rinse, repeat. The pacing is absolutely torturous, and I certainly envy anyone who was able to get more out of the narrative than the opportunity to take a nap. One thing I will praise unreservedly is the sound design. Foregrounded multiple times, this aspect of the film often becomes more important than the visuals. For example, sound edits often bridge picture edits in both directions (L Cuts and J Cuts). Similarly, we repeatedly experience the sound of one scene carrying over into the image of another well beyond the edit itself, so much so that it becomes a motif, suggesting a distortion of reality. Just prior to the dog attack, the sound becomes echo-like and the picture starts to move in and out of focus, as the camera shows Faraday in a BCU, suggesting he is becoming unglued from his environment. This also happens later on with Roderick, just prior to the fire. Perhaps the most interesting scene from an aural perspective is the scene in the nursery near the end of the film. As Angela examines the room, the distorted and difficult to identify sound becomes unrelenting (it is easily the loudest scene in the film). However, as the other characters run through the house towards the noise, all sound is pulled out almost entirely, with only the barest hint of footfalls detectable. This is extremely jarring and extremely effective, working to emphasise the dread all of the characters are by now feeling. However, beyond that, this just did nothing for me; there was nothing I could get my teeth into, I didn't care about any of the characters beyond the first half hour, the social commentary was insipid and said nothing of interest, the supernatural aspects are so underplayed as to be virtually invisible, and, most unforgivably, the film is terminally boring. Maybe if I'd read the book…