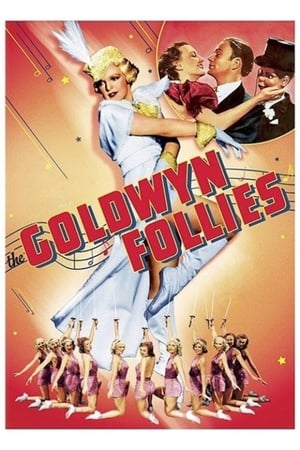

The Goldwyn Follies

There is a sense of both hesitancy and confidence in this strange work from Samuel Goldwyn. The former comes through in the need to try and sell the idea of culture in the form of opera and ballet to his audience by having it seen and endorsed through the eyes of Miss Humanity, an honest rural woman hired by studio head Adolphe Menjou to give an average person's perspective on how movies should unfold. This not-so-subtle tool provides something of a gateway for the film to introduce class acts that might have been seen as inaccessible to rural audiences. The confidence lies in the willingness of Goldwyn to throw everything into this production from comedians to a ventriliquist, from ballet to opera and moments of comedy and romance. Many of the early musicals are a mix of skits of one kind or another, from The Broadway Melody (1929) to The Great Ziegfeld (1936). That the very thin narrative adequately supports this approach is to be admired even if individual acts succeed or fail on their own merits. The comedy acts are probably the best elements eight decades later. Edgar Bergen and his dummy, Charlie McCarthy, are examples of the precision of comic timing. Bergen may let his lips move more than any other practitioner of his art but his success as a performer, and on radio, lay in the rapid fire jokes he enunciated for himself and his co-performer. The three Ritz Brothers are a force of nature - and they come on perhaps a little strongly today but it is easy to see they must have been electric on stage. Their song, 'Pussy, Pussy, Pussy' is sung without irony and is also a model for selling comedy. Vera Zorina was brought into the picture primarily as a ballerina and, yes, her controlled movement is impressive but she conveys more as a comedienne, playing a self-obsessed European actress with just a hint of Greta Garbo. Her moments of rejection, fury and ego are all well delineated. For a film made during the latter months of 1937 and released in February of 1938 this must have been a fairly early three-strip technicolor release. It lacks the bright, popping colours of The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) or Gone With the Wind the following year and the subdued pallet is effective in conveying the images without overwhelming the drama. The film within a film is clearly seen being shot with 35mm black and white cameras - clearly they only had one of the massive technicolor cameras of the time at their disposal and not a second one that could be brought into service as an on-camera prop. The dramatic and opera sequences add little and the romantic plot in particular is very conventional with a needless lack of disclosure stopping the relationship from proceeding and another character acting out of character for a moment to provide some fake frisson. This is a generally satisfactory work even if the parts rather than the sum of them is more alluring at this distance from its original release.