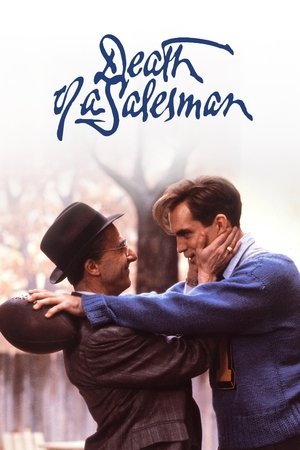

Death of a Salesman

The age of social media would be a double-edged sword for Willy Loman (Dustin Hoffman) and his prophetic obsession with what we now know as 'likes.' One of his mantras is “Be liked and you will never want.” Today this would mean getting likes, and not just by the hundreds; if possible, by the thousands. “One day I will have my own business and I will never have to leave the house,” says Willy. “Like Uncle Charley [Charles Durning]?” asks his youngest son Hap (Stephen Lang). “Bigger than Uncle Charley. Charley is not liked. He's liked but he's not well liked.” Ironically, Charley is much more successful than Willy — as is Charley’s son Bernard (David S. Chandler) compared to Hap and his older brother Biff (John Malkovich) — despite, or perhaps because of his indifference to whether or not he is liked (“Why must everybody like you? Who liked JP Morgan? Was he impressive? In a Turkish bath he looked like a butcher. With his pockets on he was very well-liked.”). Willy drew inspiration from Dave Singleman; “Old Dave would go up to his room, put on his green velvet slippers, pick up the phone and call the buyers. Without ever leaving his room at the age of 84, he made his living. When I saw that, I realised that selling was the greatest career a man could want because what could be more satisfying than to be able to go at the age of 84 into 20 or 30 different cities and pick up a phone and be remembered and loved and helped by many different people?” This could be thought of as the old fashioned way of sending friend requests, and if one wants those requests to turn into contacts — because, after all, “It's not what you do; it's who you know” — it's better to have, so to speak , a good profile picture; this is the sort of lesson that Willy instills in Biff and Hap since they were in high school (“I thank Almighty God you're both built like Adonises. The man who makes an appearance in the business world, the man who creates personal interest, is the man who gets ahead”). In Willy's world, a man's life's worth is judged by the number of people who attend his funeral; for example, “When [old Dave] died, hundreds of sellers and buyers were at his funeral. Things were sad on many trains for months after that." As for his own funeral, Willy dreams of a “massive” one: “Oh, they'll come from Maine, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire. All the old-timers with the strange licence plates. [Biff] will be thunderstruck ... because he never realised I am known. Rhode Island, New York, New Jersey, I am known!” All of this is as illusory as a Facebook profile, as are the 'memories' that Willy 'shares' with us, which represent an idealized view not only of the past but also, thanks to Willy's incipient senility, of the present. The greatest irony of this film, directed by Volker Schlöndorff and adapted from the play of the same name by Arthur Miller, is Willy's inability to see that if people don't like him, it's not because he’s "very foolish to look at", but due to the simple fact that he’s just not a likeable person: he yells at his wife Linda (Kate Reid), whom he used to two-time on his business trips — when Biff catches him red-handed with another woman and loses his considerable respect and admiration for him, Willy accuses him of throwing his life away to spite Willy, who had placed high hopes on Biff's athletic prowess (Biff, however, never tells his mother what he saw, at the cost of having her resent him for his coldness towards his father) —; he constantly hurls insults at Charley, and even questions his manhood, ("A man who can't handle tools isn't a man"), but has no problem taking Charley's money (but not a job that would most likely be a sinecure when Charley offers him one after Willy has been fired); etc. All things considered, Willy is the kind of 'friend' who is shocked when you block him, but then sends you a request from a different profile.