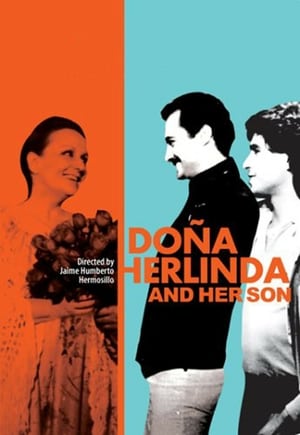

Doña Herlinda and Her Son

Doña Herlinda and Her Son, the 1985 film from writer/director Jaime Humberto Hermosillo, is not only a funny, warm gay romantic comedy, it also marks the first time that a Latin American film depicted gay relationships positively. I enjoyed this film a great deal, and recommend it. The story, and filmmaking style, are both effectively simple. The wealthy widow Doña Herlinda (played with beguiling warmth and slyness by Guadalupe Del Toro) dotes on her somewhat spoiled physician son Rodolfo (Marco Antonio Trevino), who is romantically involved with a younger man, music student Ramón (Arturo Meza). When Doña Herlinda decides it's time for her son to take a wife – while still keeping his lover – she uses all of her considerable maternal wiles to put an ingenious plan into motion. With her huggable pear-shaped demeanor and butter-wouldn't-melt smile, who would suspect that she is actually a romantic Machiavelli. (Or, if you prefer, a low-key Auntie Mame; she's even been called a Latina Yiddishe mama!) I don't want to give away too many plot points – I found some of them delightfully surprising – but I will say that, by the film's end, Doña Herlinda has brought the greatest possible happiness to the greatest number of people... including herself. Despite the title, the film is more about "her son" than Doña Herlinda. The opening sequence, in which Rodolfo visits Ramón at his seedy boarding house, is not only sweetly sexy, and believable, it also shows the deep connection between the two men. And although Doña Herlinda is the larger-than-life character, it is Rodolfo and Ramón's love which grounds the film. Hermosillo excels at including telling – and witty – details of their relationship. Playfully highlighting Rodolfo's immaturity, Hermosillo hangs a huge poster from the action film Mad Max over his bed; and he and Ramón make love inches from a Star Wars action figure (Boba Fett the bounty hunter). In a sublime comic touch, in the next room Doña Herlinda listens to Bach, and the lovers, while flipping through a bridal catalog... smiling. Hermosillo does not shy away from the raw emotions brought up when Rodolfo springs the news on Ramón that he is going to marry Olga, a woman hand-picked by his mother. Not only do we see Ramón's pain and Rodolfo's ambivalence, Hermosillo spends much of the last half of the film exploring, with depth and understanding, how the two lovers come to navigate the complexities of their new situation. Another strength of the film is that Hermosillo presents Olga – in a subtle performance by Letícia Lupercio – as a well-developed character, not as the caricature you might expect: think of the Mr. or Miss Wrong's in countless screwball comedies. Olga is personable, feisty yet open-minded; she even works for Amnesty International. Not only do we see that she and Rodolfo are good friends (they had better be!), late in the film there's a wonderful scene in an ice cream shop between Ramón and Olga. Although neither speaks The Truth about their situation, we see real healing begin to take place between Rodolfo's lover and wife. For all the film's warmth and good spirits, I am disturbed that it has more "don't ask / don't tell" situations than any US mlitary base. It never shows why Rodolfo has to bow to middle class conformity, especially considering the financial independence of his family. Like the society in which it was produced, it goes along with the assumption that a man of Rodolfo's age must marry a person of the opposite sex. So much in Doña Herlinda of real importance is never spoken about, primarily the fact that Rodolfo and Ramón are not only gay – as everyone knows (wink wink) – but represent the only truly loving couple in the film. Yet despite all the silence, this is not the sombre, repressive territory of an Ingmar Bergman film; it's colorful, sunlit Guadalajara, with its mariachi bands and spacious homes. And while so much goes unspoken, it is also clear that Doña Herlinda has no problem with her son's being gay. From the start she fully accepts Ramón as a second son, even telling him to move in, since her son's "bedroom is very big." Later, when Rodolfo is away on his honeymoon, Doña Herlinda does everything she can to cheer up Ramón, even devising the plan which becomes the film's ingenious, if controversial, resolution. There is real generosity of heart in Doña Herlinda, both the woman and the film – but not a word acknowleding that her son and Ramón are more truly "married" than Rodolfo and Olga. One reason why Rodolfo and Ramón are so effective at holding the film together is that they do talk about their feelings – which we see dramatized with considerable depth – and work through them. They are the most authentic characters in the film; the ones we want to see live happily ever after. Yet even they never mention the social, let alone political implications of their relationship. I am not saying that the film should have been some sort of political tract. But what makes all its silences so disconcerting is that they permeate, and undermine, a film otherwise brimming with vitality. If you are looking for a positive spin, you could argue that Doña Herlinda's many unspoken assumptions – including the still-timely one of gay "invisibility" – make it an ideal film to discuss at length with friends. Dramatically, I think the film would have been more effective if Rodolfo and Ramón's love had dared to speak its name. Then the story could have moved in some compelling new directions, perhaps both more farcical (which could have been fun) and emotional. I would have liked to see how Doña Herlinda, and Olga, deal with Rodolfo's being openly gay. Yet we should remember that this film was historically important in its positive positive depiction of gay relationships. Hermosillo said at its 1985 release, "The most disturbing thing about the film to some of the 'machista' audience has not been the sex in the film but the tenderness - it's so tender, the relationship between the men, and some cannot accept that. I think that's terrible." Consider how far GLBT cinema, and people, have come in less than two decades. Some people have criticized Doña Herlinda's so-called "amateurish" filmmaking. I disagree. The simplicity of visual design – few films use medium shots so relentlessly – works well with this "straightforward" story. And Hermosillo, in his other films, is highly regarded for his creative use of cinematic style. Hermosillo, raised in Guadalajara (where he sets many of his films), began directing in the late 1960s. Most of his (to date) 26 films were produced through independent companies; in fact, Doña Herlinda star Guadalupe Del Toro also financed the film, which was co-produced by her son Guillermo (recently the director of such acclaimed Hollywood hits as Mimic and Blade II, and the exceptional fantasies The Devil's Backbone and Pan's Labyrinth). Hermosillo is openly gay (still unusual in conservative Mexico), and often makes films which deal with same-sex issues, including 1977's La Apariencias Engañan (Deceitful Appearances). But his popularity in his native country may be attributed to the sophistication he brings to his tales about the Mexican middle class, exploring their desires, and fears, with both wit and understanding.